The Age of Wizards and Witches

What is "magic" today, plus a guide about how to practise it

What is magic? Examples of magic include flying without wings but with fairy dust like Peter Pan, moving objects with your mind, healing wounds, or shooting lightning from your hands. While the definition of magic has changed across centuries and traditions, we can generally argue that magic is the ability to accomplish something out of the ordinary. Another characteristic of magic is that it is exclusive. If we think of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales, or even those of our own culture, there are very few wizards in the population: there are plenty of peasants, many knights, a few princes, only one king, and often just one wizard. The possession of magic is therefore just as exclusive as the power to govern.

You could say that magic is a gift. The Sword in the Stone (the 1964 Disney film version) opens with a struggle between pretenders to the throne following the death of the King of England, who left no heirs. A mysterious sword is stuck in an anvil on a stone; whoever manages to pull it out will rightfully be the new ruler. Everyone attempts the feat, but physical strength is not enough: one must have the gift. Centuries pass and the country falls into chaos; a tournament is held to decide the new king. Wart (Arthur) is trained by Merlin the Wizard, but on the day of the competition, he forgets his weapon at a closed inn. almost by chance, he sees a sword stuck in a now-forgotten stone and manages to pull it out: it is the gift. He becomes the rightful new King of England. The sword is the recognition of a divine birthright, not something that can be acquired.

If we look at other cultures of the past, magic is always something exclusive. Few people had a privileged relationship with the deity or deities: only the Pharaoh had the power to pray for the Sun to rise; in the Mediterranean, there were various oracles (Delphi, Cuma), but they were still few compared to the population and the kingdoms of the time.

On the other hand, if a gift is widespread, it ceases to be a gift; an inflated power is no longer exclusive and loses its value. Imagine, for example, knowing how to swim. If no one knows how to swim, the person who can do it possesses a power superior to the others. If, however, everyone knows how to swim, swimming is no longer a gift.

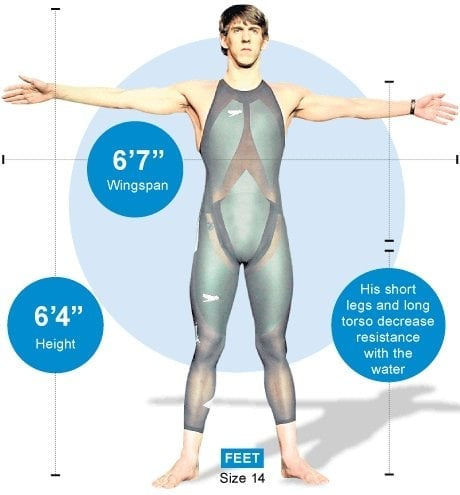

However, swimming particularly fast can be a gift. Think of the most famous swimmer of this century, the 23-time Olympic gold medalist, Michael Phelps.

Many have pointed out that Michael Phelps’ gift lay in his body proportions, which were particularly suited for swimming. For example, his wide torso and shorter legs provided less hydrodynamic resistance (source of above picture). Perhaps Phelps also had another gift: determination. He swam 13km a day, spending 5-6 hours daily in the pool, and consumed between 8,000 and 10,000 Kcal a day—four times the standard amount for an adult male. I challenge anyone to do something similar. Personally, I believe anyone can achieve extraordinary success if they follow his training and diet regime (under professional supervision, of course); maybe they wouldn’t beat Phelps’ records due to the uniqueness of his body, but they would still achieve results superior to most people. Yet, very few would be willing to do it or would have his willpower.

In a world where the ability to swim is easily accessible, a major difference is, therefore, determination. That said, it is not the only winning element. I see an increasing spread of silly success narratives based solely on willpower, often with the aim of mocking those who have less of it. Sometimes I read that if you are in financial trouble or aren’t a “successful” person (but then, how do we define success?), then it is your fault because you didn’t believe enough in what you were doing or you didn’t try hard enough. These are great absurdities, often peddled by modern-day snake oil salesmen selling empty, generic video courses. They forget the “luck” factor (and “fortuna” in Latin means “fate” or “chance,” just as chance governs the result of a roll of the dice).

The gift is, therefore, a unique quality, but beyond possessing that quality, one must put it into practice; training is required. Modern magic is thus composed of two elements: the initial gift and the exercise. Harry Potter was born a wizard, but he wouldn’t have become a skilled sorcerer had he not gone to Hogwarts. Similarly, Giuseppe Verdi was born with talent, but he wouldn’t have become a great musician without his mentor Antonio Barezzi, who financed his studies.

Let’s leave fairy tales behind and enter the real world. Let’s look at the world of knowledge. Once, culture was the prerogative of a few people and was difficult to access; it was a highly exclusive gift. This stemmed both from widespread tradition and logistical problems, such as the intrinsic deterioration of books: it was only in the 1400s, with the invention of the printing press, that text became easily replicable; before that, everything had to be copied by hand. Even after solving the problem of owning the text, it wasn’t until 300 years later, during the Enlightenment, that the idea of knowledge being free and accessible to all began to spread. Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie moved in this direction, but the cost of purchasing the volumes was still burdensome.

Today, public education represents the democratization of the gift of culture. Anyone can access knowledge for free (or at least at a very low cost); anyone can learn to learn. Effectively, since public school was introduced, everyone is born a wizard; the difference lies in the practice of magic, that is, in the effort dedicated to acquiring knowledge.

A further boost comes with the Internet. Public school gives me the gift of knowledge, but I still listen to only one teacher, have only one type of explanation, and follow standard paths. The Internet flips the situation; thanks to the web, knowledge today is incredibly easy to access compared to before. I can access multiple explanations and many more sources, and the cost of the Internet is practically nil compared to the benefits offered. For example, national encyclopedias are consultable online for free; many universities offer free online courses; there are other free courses on YouTube, ranging from the most basic to the most advanced levels.

If magic consists of a gift and exercise, from the perspective of knowledge, thanks to public schools and the internet, today everyone has the former; they only need to apply the latter. This goes beyond mere academic culture; it applies not only to humanistic or scientific knowledge but also to experiential knowledge. YouTube is full of videos on how to improve your flexibility, how to fix household pipes, how to tend a garden, or infinite practical things. We have an immense library of human knowledge at our disposal—Wikipedia is just the tip of the iceberg; one simply needs to want to obtain that knowledge.

We live in the only phase of human history where “where there’s a will, there’s a way” is truly true. However, the reverse does not hold: meaning, it’s not true that if I can’t, then I didn’t want it enough. There can be a thousand reasons to want one thing, just as there are a thousand reasons to want other things or not want them at all.

Life isn’t just knowledge, life isn’t just useful or practical activity; life is also sleeping and resting. From my point of view, man’s highest aspiration shouldn’t be success, partly because success is a generic concept that depends on cultural factors and the era in which one lives. The true highest aspiration is balance—having what you need and not wanting more; that is living well.

The difficulty lies in understanding what one truly needs, distinguishing true desires from ephemeral whims. “Where there’s a will, there’s a way” only makes sense if practiced for the life that each individual personally wants, not for standards that aren’t ours or are unreachable. Who cares about a brand-new car if you don’t like cars? Who cares about having a sailboat if you get seasick? Who cares about ski vacations if you don’t like skiing? Who cares about having an ultralight bicycle if you don’t like cycling? Who cares about running a marathon if you don’t like running? The great tragedy of globalization is the attempt to seek standardized lifestyles at the expense of individuality.

If today we are born with the gift of access to knowledge, then everyone’s aspiration must be to practice in order to have the life they truly want. We should take Merlin the Wizard as an example, who, despite having infinite magical powers, did not live in a Palace made of gold; perhaps because he didn’t truly want it.