The Queen's Broken Mirror

How the West Clumsily Tries to Rediscover Itself

This article is part of the series “The Red Thread of Our Century,” dedicated to analyzing the relationship between the individual and contemporary society. To catch up on other readings, read here (currently only in Italian, I’m traslating the other articles in English): Il Filo Rosso del nostro secolo

«The Queen stepped out onto the balcony of the Castle to watch the last blue light of the Sun on the horizon. The view was stupendous, on a hill dominating the surrounding countryside, with a dense forest on the right and one of the cleanest lakes in existence on the left. The Sun offered its final farewell, setting the horizon ablaze, then leaving space for that periwinkle color she loved so much. During the night, that Sun would disappear, the Moon would rise, until the following day the cycle of peace and beauty would begin again. A young man with blond hair used to spend his days at the Royal Pond; she saw him as he walked away, taking the path that led to the nearby village. He spent entire days staring at the bottom of the pond, who knows why.

She closed the shutters and put on her nightgown, blew out the candles, and it was dark.

The following day she was commanded awake by screams coming from outside. Annoyed, she threw off the covers, slipped on her ermine slippers, drank a glass of water, and approached the window to understand the origin of the screaming. Through the crack in the shutters, she observed the young man from the Pond losing his mind: he was beating his fists against his head, churning the water with his hands, tearing up the grass, running in circles, and stuffing thorny stems from the rose garden into his mouth. She was disturbed by that vision; normally he was such a beautiful and silent young man, she believed he loved that landscape where he spent his days. Nothing like this had ever happened. However, she decided that this event would not disturb her morning awakening ritual.

She stepped away from the window and approached the vestibule next door. In the center of the space reigned an ancient gift from a distant wizard, a mirror surrounded by a frame finely inlaid with gold and lapis lazuli. The Queen closed her eyes and moved, dragging her steps delicately. “Mirror, mirror on the wall, tell m... Mirror?”. Her tenderly half-closed eyes opened suddenly; she saw that the Mirror reflected nothing. She moved and tried to observe the object from different angles. It wasn’t a matter of dust or cleanliness; she simply saw an opaque black. She lit the candle next to her dresser, took it in her hand, and brought it close; she noticed the glow of the flame lighten the surface of the Mirror, yet without any reflected images. What was happening?

“Teresa!” she screamed, calling the housekeeper. “Teresa! What is going on? Come here!”. The woman entered in a rush, wearing her service dress; only her hairstyle was different, she didn’t have her usual bullet bun but a jaunty low chignon. “What is wrong with the Mirror? And how are you wearing your hair today? Bring me another mirror immediately!” thundered the Queen. The woman clasped her hands and began to tremble. “I beg your Majesty’s pardon, it is just that... it is just that... this morning I found my mirror downstairs, but I am sure that... Ah!” she screamed, looking at the opaque black between the inlaid frames. “I don’t care! Bring me a Mirror and be quick about it!” her interlocutor retorted. The housekeeper rushed a curtsy and left the room. Immediately, the housekeeper opened a trunk containing ancient gifts from a vassal who had died some years prior; she remembered there was a copper mirror. It was a bit ugly and not very valuable, which is why it was locked in the chest, but functional nonetheless. It was wrapped in a black cloth; she untied the knots and looked at it: it was completely green and aged, it reflected nothing.

They discovered that no mirror worked. Throughout the castle, the mirrors were as black as the Queen’s, others had broken into pieces so small they reflected nothing. Outside, the situation was far worse: the blond boy continued to rage. The gamekeeper had reached him to punish him with a good thrashing for that commotion, but had failed to catch him. Furthermore, the water in the Pond was unusually turbid and full of sludge; the bottom could not be seen, and the Sun was not reflected. The Queen ordered all the subjects of the kingdom to bring her even the smallest of mirrors, but it was all in vain; few people could afford such objects, and even the barbers had woken up without that important tool of their trade. Distraught at not being able to see herself, she continued to ask the maids how she looked; she was expecting visits after noon and had to be presentable. All the maidens said she was, as always, the fairest in the Realm and that she shouldn’t worry. The Queen then calmed down, but a doubt remained in her heart: is it truly so? How could she verify her beauty without being able to observe herself? She was forced to rely on the rumors and compliments of her subordinates; were they reliable?

At noon, an envoy from the Duke arrived to be received, handing the housekeeper a letter stating that for personal reasons he would not be coming. He looked her up and down, noticing her hair which had by now come completely undone, but he dared not say anything. The envoy wore a perfect white wig; the housekeeper envied his composure. The Queen had spent the whole day restless. Dinner was served on an opaque gold plate. Opaque! This too! How was it possible? She no longer had an appetite. She raised her gaze and headed towards the exit of the hall, when she looked at her mother’s portrait, which triumphed above the hall’s fireplace. The portrait! Immediately she ordered all the painters of the Kingdom to be called to work; they were to come as soon as possible to each create a representation of the Queen as faithful to Reality as possible. If she could not see herself, the masters of truth would capture her every essence. In the following days, she wore the best wig she owned to ensure final success; she posed from morning to evening, motionless as a wax statue, awaiting the results.

After a month, the verdict arrived. The painters were lined up in the throne room, each holding their canvas covered by a white cloth. “Step forward, the first, show me the result.” It was an elderly gentleman of 50 years; he could barely stand but was renowned for the fineness of detail in the paintings he executed. He removed the white cloth: the painting depicted the Queen in a composed frontal position. The body proportions were correct, only the nose was a bit more arched than the Queen remembered. She huffed and called the second painter. The master had chosen a three-quarter stance, with hands resting on a sphere symbolizing power. The gaze was directed far away, to a point outside the canvas. The nose seemed normal, only the chin was squarer than usual. That detail wasn’t in the first painting. The third painter arrived, with yet another pose and a different detail. In the end, all 20 painters who had participated in the endeavor placed their canvases on easels; the Queen passed in front of them all to choose the best one. The problem was that the subjects were all different! Disproportionate hands, clumsy cheeks, hunched shoulders, each had a different defect; above all, there was no commonality among the depicted defects. How was it possible? The Queen remained silent and put her hands in her hair; she lost her grace and composure, tearing the wig off her head and screaming in pain. What was she truly like? Had the painters each made a mistake in a different way? Was she the sum of everyone’s defects, or was she pure of imperfections?

The housekeeper looked at the distraught Queen; she had understood her state of mind and was also incredulous at the bizarre result. Then she thought for a moment: if those imbeciles hadn’t been capable of making a good portrait, that didn’t mean that faithful representations didn’t exist in the past. She approached the Queen and communicated the suggestion; the ruler appreciated the idea. They thus recovered a portrait from her maidenhood; the Queen ordered all existing currency to be melted down and new coins to be minted immediately with that beautiful portrait.

A few months later, the parish housekeeper was emptying the offering baskets and counting the money. She was a very intelligent woman; she knew how to read and do sums. She hadn’t seen well from a distance for years, but up close she had unparalleled sensitivity, perhaps even better than when she was a girl. She observed with her index finger and thumb the coins that had arrived, all identical with the same portrait. She had never understood why, after the order for the new coinage, the Queen had chosen to depict not herself but the King Father’s mistress, who at the time had caused great embarrassment to the entire court.»

(Text taken from “Stories of the Sunset” [Storie del tramonto], by A. Vindingia, Demi Editore [0])

Hegel, a German philosopher of the first half of the 1800s, writes of living in a period of gestation and change [1]. At the beginning of the 1900s, in “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” Nietzsche writes instead of a madman who comes into the city screaming that God is dead and that we, human beings, have killed him [2]. Much of what we see happening in Italy today depends on the death of God. Fasten your seatbelts.

I have always viewed Hegel and Nietzsche’s thoughts as consequential, in both a temporal and logical sense. Far be it from me to want to teach you a philosophy lesson (I wouldn’t have the skills) and far be it from me to want to be aphoristic (I must already thank you if you have reached this line of the article), but it is as if Hegel warned us of something immense about to be born in Western thought in the 1800s; Nietzsche picks up the theme and argues that that “something” is nothingness, or rather the death of beliefs (from which the creation of new values follows). Nietzsche’s God is, in fact, the representative of the beliefs upon which Western civilization, as it was known until then, was founded.

Clearly, over the centuries, man has seen various creeds alternate, just think of the alternation of religious cults. Let’s imagine taking a trip back in time to Rome, the Eternal City. In 700 BC, we see temples and shrines dedicated to Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. If we move to around 100 BC, we see instead a greater Hellenistic influence, with Jupiter, Minerva, Diana, and other deities. 100 years pass, and the cult of the emperor arrives. If we jump to 150 AD, we see the first Christians spreading the Gospels and hating the symbol of the cross (because thieves died on the cross and it was a dishonor). In 306 AD, the Council of Elvira of the Church Fathers forbids priests from marrying and having children (and if the Council deemed it appropriate to address the issue, there were likely many priests with wives and children at the time). In 494, in a letter, Pope Gelasius I explicitly forbids women from giving the Eucharist; again, it is likely that there were priestesses to necessitate clarifying this. If we arrive in Rome at the time of Dante, we see happy families accompanying spouses to sign the marriage contract at the notary; marriage is in fact associated with having children, with fornication; it is something dirty. Contracts, after all, are made at the notary. Perhaps from the Catholic Counter-Reformation in the 1600s onwards, we see celebrations similar to ours, except for the mass celebrated strictly in Latin or communion which, until 1905 with Pius X, was taken few times a year and not every Sunday. Changes of creeds, of traditions, changes of cults.

However, what Nietzsche describes is not a change of creed. It is the sky of Asterix and Obelix falling on our heads. Perhaps it is the disappearance of the sky itself. Let’s think of Galileo Galilei, 1600. Those who have read or seen Brecht’s “Life of Galileo” in the theater know that the Pisan scientist essentially opposed a creed (heliocentrism) against a creed (geocentrism), like sword against sword, mace against mace, testudo against testudo, without any particular openness to relativism or criticism. Conversely, the Cardinal Inquisitor on one hand wants to deny heliocentrism, but on the other asks Pope Urban VIII that Galileo’s astronomical charts be used because they are better for navigation than the others in existence. With Nietzsche, instead, we have the disappearance of belief. Don Quixote is mocked because he mistakes windmills for giants; a Nietzschean Don Quixote, however, would brandish his sword and slash at the air: neither the windmills nor the giants exist. If the giants don’t exist and there aren’t even windmills, what is the point of fighting? This is one of the consequences of the death of God.

Let us now leave philosophical dialogues on the grand systems of the world and land, finally, on the case of Italy, on the Queen’s broken Mirror. In the passage I quoted to you, taken from the novella “8 Hours to Midnight” by Adele Vindingia, the Queen of Snow White can no longer see her reflection and Narcissus loses his mind. Seeing herself no longer, she asks painters to portray her but cannot accept how the other painters see and represent her. She finally ends up believing she has the same appearance as a portrait from the past, so she orders coins to be minted with that portrait. In reality, the portrait was of the king’s mistress, but to appease her wrath, the housekeepers or other subjects say nothing.

Our local situation is very similar in certain aspects. What is perceived is a lack of meaning. There are many foundational questions about our culture to which the answers may seem weak. For example, what is Italy? One could say it is the country where Italian is spoken; well, look at what language is spoken in Veneto, in South Tyrol, or in the heart of Sardinia and then give me an answer. More generally, what we knew as Western Civilization is at a crossroads. Let’s start from the foundations: what is the geographical boundary of “Western”? Sarajevo? Tel Aviv? Constantinople? Moscow? Samarkand? Much of Western culture was born after the bloodbaths of the second post-war period, from universal declarations. We moved culturally towards the recognition of the dignity of all people, creating an organization for the continuation of peace (the UN), an International Court based in The Hague. We believed in scientific cooperation, creating a supreme authority for health (the World Health Organization), a body with the best medical and clinical minds on Earth to protect the health of all humanity. Then, the moment the WHO declared the start of the Covid epidemic (January 30, 2020), we completely ignored it; the first government measures arrived a generous month later. Cyclically, there are those who accuse the WHO of overestimating the risk of epidemics, only to lick their wounds after the damage is done.

In fact, the sense of “Institution” is being lost; we see their transformation from simulacra to good luck charms; one profanes, profanes, profanes. It is not a new phenomenon. The Lombard independence activists of the 90s declared they wanted to use the Tricolore flag as toilet paper. At the time of Brexit, many activists tried to burn the EU flag (with great difficulty and embarrassment, because due to EU fire safety regulations, the flags are made of fire-retardant material). If the institution loses authority, there is no sense in respecting it either. If I don’t appreciate art history, I have no reason to respect a temple of an ancient civilization; on the contrary, I destroy it. Thus it happened in Palmyra with ISIS [3].

Or, new values pretend to destroy the old ones. The collector Martin Mobarak in 2021 buys a Frida Kahlo work worth €10 million, publicly digitizes it as an NFT (i.e., takes a high-resolution photograph and spreads the photo on the internet, protecting private property with blockchain technology) and then burns it, declaring that by now that work lives only in the metaverse. It seems that from the sale of the digital file he raised €11,000—a great deal [4].

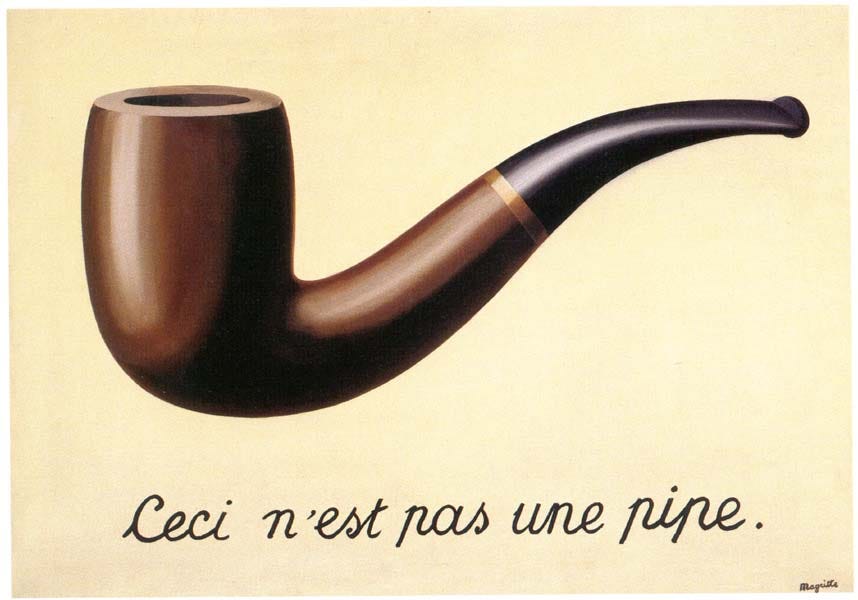

Duchamp said (and painted) “Ceci n’est pas une pipe“ (”This is not a pipe”); the painting is a representation of the pipe. This techno-futurist champion Mobarak essentially digitized the representation of the painting (a photo of the painting is still a representation, it is not the painting) and destroyed the original. It is incredible how the wondrous and progressive destinies of technology can be calmly described with the categories of the 1900s; where is the novelty?

Faced with continuous “Whys?” without answers, faced with the (presumed) victory of opinion against truth, the West wants revenge and tries to reaffirm its own values. The problem is that, exactly like the Queen, it does so in an almost grotesque way. Let me illustrate a recent example.

I believe that Minister Giuli is doing a good job promoting culture in Italy, but to what end remember a battle of the Second Punic War that took place more than 2000 years ago? But why? [5]

(The text says: “1/5 I had promised that on the second of August I would attend the two thousand two hundred and forty-first anniversary of the Battle of Cannae, and I kept my promise.”)

We are living in a West that tries to relaunch an idea of itself by relying on the glories of the past, ending up betraying itself. It is certainly a good intention; the problem is doing it in an excessive, baroque way. Who are we today? Who have we been? Who will we be? It is difficult to give an answer but I will try, in the next articles of this series. Today I wanted to define the starting point, highlight the lack of Creed and some clumsy attempts to put patches on it. And if we want to “save ourselves” as Western culture, I will illustrate to you that it will not be enough to have patches: we will need to sew them and give them a unitary sense.

Homework challenge: if you know Italian langue, try to write an anagram of Adele Vindingia, the author of the story reported above. Write the answer as a comment below or on my social channels.

Sources:

[0] “Storie della bobò” [Stories of the bobo], Adele Vindingia, 2014, Demi Editore

[1] Preface to “The Phenomenology of Spirit”, Hegel

[2] “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”, Nietzsche, Adelphi [3]

“ISIS publishes photos of the destruction of the Temple of Palmyra”, August 24, 2015, La Stampa; accessed December 3, 2025 [4]

“Miami, burned a 10 million Frida Kahlo work to transform it into NFT: only the proceeds went up in smoke”, Emanuela Minucci for La Stampa, November 11, 2022, accessed December 3, 2025

[5] “Minister Giuli’s strange commemoration of a battle of the wars between Rome and Carthage”, Il Post, August 4, 2025, accessed December 12, 2025